Lessons From Market History: Price Does Matter

In This Issue:

- Looking at the premium of US technology stocks

- Drawing lessons from market history

- Great companies do not always make great investments

- The price you pay for an investment matters

With nearly 10 months of experiencing the duress of COVID-19, the global economy continues to adjust and adapt to a whole new frontier. It is hard to find a sector of the economy that is back to normal – as defined by pre-COVID operations. What we can say is that companies in every single sector are seeing a new normal and are adapting their operations to take into account the safety of their customers and employees. But compared to the dire consensus of most economists earlier this year, the global economy has surprised many with its ability to snap back as far as it has. However, as noted in previous commentaries, the road back will be uneven.

Clearly, the term “new normal” does not adequately describe the scale of change that has been brought to bear by the pandemic upon households, governments and businesses. No corner of the global economy has been left untouched. While the changes we have seen in 2020 are certainly significant, the financial markets are signaling that they are increasingly comfortable with what they are seeing. The confidence fueled by ultralow interest rates and generous amounts of fiscal policy in the forms of income payments and tax relief are showing up in the market values of global stock markets.

US Equities Continue to Lead

For several years, US equity markets have been moving higher relative to their global counterparts despite being somewhat more expensive. However, the level of overvaluation of US equities is somewhat misleading.

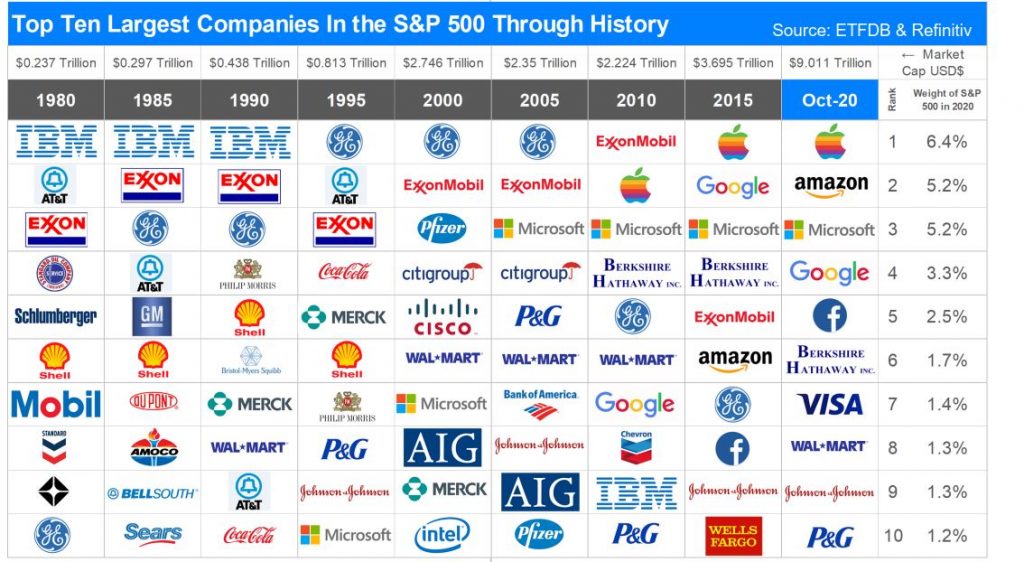

Measures of market valuation are compiled by weighting each company according to its size (market value); therefore, the larger the company, the greater its ability to skew a market’s valuation. For example, in the US, the S&P 500 is dominated by US technology giants such as Apple, Microsoft, Google and retailer Amazon. A small handful of companies are skewing the

US stock market’s valuation upward with their own premium valuations. There is no doubt that these companies should trade at a premium to the global equity market. They are truly unique companies without any peers to be found anywhere else in the world. The only question is “How much is too much?” when it comes to the price which investors should be willing to pay in order to buy the shares of these companies and still be able to earn an acceptable rate of return.

As the recovery from COVID-19 began this past Spring, a must-have mentality took over and investors began to chase the US technology sector with a steady stream of buying. As price momentum in these companies rose higher, it attracted even more buying interest by investors chasing price momentum. As some of these companies saw their market values soar past $1 trillion USD, investors began to abandon most other sectors of the economy in order to try to benefit from the price momentum in the shares of technology companies.

Currently, the US technology sector represents 28% of the market capitalization of the S&P 500 stock market index. This has caused some alarm amongst market analysts who worry that US markets are increasingly becoming concentrated in a handful of companies – similar to what happened in the period leading up to the technology sector meltdown in March 2000, which kicked off a multi-year bear market in global markets.

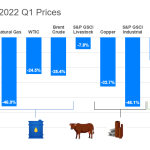

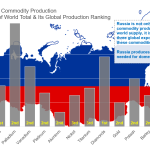

Like now, the technology sector in 2000 was the largest weighted sector in the US due to the immense growth of companies such as Microsoft, Intel and Cisco Systems. By March 2000, the technology sector selloff began and it pulled down the rest of the stock market with it. But in the midst of that carnage, a bull market in the commodities sector (e.g. oil & gas, copper, gold, steel, etc.) began to take root. But for several years, seemingly nobody noticed as investor interest remained on technology.

While there are some similarities between then and now, the US technology sector is much more profitable today than it was during the “dot com” bubble years and the higher valuations are being supported by much lower interest rates today. Therefore, it would be a mistake to draw too strict of a parallel between then and now.

Reasons for Caution

As great as the US technology sector companies are, they are not without risk. History shows that many great companies get bid up to such a premium valuation that they are not able to reward their shareholders with the rate of return expected by their shareholders. In short, great companies do not always make for great investments.

Of the ten largest companies in the US, six are technology companies (Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Nvidia and Visa). If we include retailer Amazon.com, these seven companies account for almost 25% of the US stock market. History shows that dominant companies that reach the top of the market capitalization ladder are not immune to being knocked off of their perch and sometimes, it is a long way down.

As the Table shows, companies that were at one time the most valuable companies in the US stock market fell down and many are still struggling to get back to their former status. For example, all throughout the 1980s, IBM was the most valuable company in the US and today it is valued at a 50% discount to the US stock market as measured by the S&P 500. It has gone from being the most valuable company in the US to number 57.

Today, the most valuable company in the world is Apple. It has gone from being a company that at one point in the 1990s traded for less than the value of the cash on its books to a market value of $2.4 trillion. Given its accomplishments, it is hard to argue that Apple does not deserve to be the most valuable company in the world. But carrying a market value of $2.4 trillion means that the financial markets are requiring Apple to continue growing its earnings at ever faster rates. Being awarded a gigantic market

value brings with it equally large expectations about future profitability. It took Apple 42 years to get to $1 trillion in market value but less than six months to get to $2 trillion despite Apple’s profit growth being largely stagnant in the last few years.

For shareholders, it means Apple must continue to dominate its space, come up with new products and grow its subscriber base for its services at sufficient enough levels that allow it to continue to add on to its $2.4 trillion market value. Otherwise, it may in time become another great business that generates poor shareholder returns. If that were to persist, then Apple could find itself supplanted atop the market value rankings by another company—as happened to Exxon, GE, AT&T and others.

Given its $2.4 trillion market value, if Apple wants to continue to reward shareholders by buying back its shares (share buybacks enhance shareholder value by reducing the supply of shares) at current levels, it could spend $100 billion on buying its own shares back and only reduce its share count by 4%. This is one example of how much cash a giant such as Apple must generate to be able to continue enhancing shareholder returns.

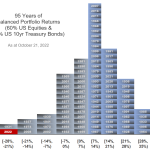

As the chart above shows, at least some of today’s largest and most sought after companies are likely to be pushed aside in the future. It might seem to be an impossibility today that Apple or Microsoft could be knocked out of the top 10 largest companies in the US. But we should remember that from January 1, 2000 to January 1, 2015, Microsoft had an annualized total return (price gains plus dividends) of 0.69%. Said another way, an investor who held Microsoft for that 15 year period earned less than a certificate of deposit (CD) at the local bank would have earned. Yet, in that time period, the company was able to reduce its share count by about 20% and raise its dividend substantially while almost tripling its operating cashflow. In short, Microsoft did everything a great company could hope to do but its premium valuation during the “technology stock bubble” of the 1990s had to be un-wound which hurt its shareholders over many years. But it did eventually turn Microsoft into an attractively-priced investment. The irony is that by this time most investors shunned the value-priced Microsoft because investors were “fed up.” Simply put, for investors who paid too much for this great company, they made virtually no return for 15 years!

It would be logical to think that Microsoft’s story is a one-off event related to the technology sector collapse. But the same thing happened to Walmart in that time period (see insert). While there is no single reason for why this phenomenon occurs, one reason is that investor expectations rise too high—along with the share price. That is to say, the higher the premium valuation on a company’s share price, the higher the market’s expectations that the company must meet for growth. Eventually, a collective “come-to-its-senses” tide washes over the market and the most popular companies see their share prices undergo “mean reversion” (i.e. a cooling off of investor enthusiasm for the company’s shares). This process then begins the process of an erosion of the previous premium valuation. As history shows in the case of great companies, such as Coca-Cola, Walmart, Microsoft and others, this process can take a decade or longer.

During the mean reversion process, these companies all continued to excel at what they did and would still be considered world-class in their respective industries. The only difference is that the markets realize at some point that they are already priced as world-class companies. Like changes in fashion trends, there is no centralized structure that governs when popular companies go out of style—they simply do. Then, when the shares of these companies become disliked they become cheaply priced and the cycle begins again.

Market History: Growth vs. Value

One of the unique things about the US stock market, unlike most other countries’ markets, is that leadership changes as new industries and new companies are created. It was within the last two decades that Google and

Facebook were a concept. Today, they are amongst the most valuable companies in the world.

Investors must recognize that great companies do not always make for great stocks to own and not all bad stocks are representative of a bad underlying business. The key is that the price paid for a stock matters and leadership in the markets will change.

While the technology sector is getting the most attention from investors, other sectors are offering very attractively valued companies that are being largely passed over. Many of them meet the test of being great businesses

priced attractively. A review of market history says that it is prudent now to at least begin to assess when the leading technology stocks will begin to lag. However, history says most investors will ignore history and stay with what makes them most comfortable.